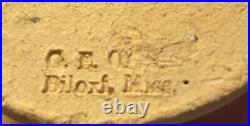

George E. Ohr Art Pottery Mushroom Novelty Bank, signed, ca. 1890's-1900's

3" h × 4" w × 3¾ d (7.6 × 10 × 9.5 cm). Excellent condition - please see photos. American and European Ceramics, Item 267. About George Ohr (from Rago Arts website).

Born to Alsatian and German immigrants in Biloxi, Mississippi in 1857, George Ohr learned the art of blacksmithing from his father, was apprenticed first to a file cutter, and then to a tinker, worked in chandlery and became a sailor, and otherwise knocked about until 1879, when his childhood friend Joseph Meyer invited him to New Orleans to learn the art of pottery. Meyer was a traditional potter, of the type common throughout the country prior to the industrial revolution and well into the 20th century in much of the rural south.Ohr absorbed Meyer's folk aesthetic and ultimately transformed it into something totally original. His vessels are technical tours de force, unexcelled in the thinness of their bodies and the control with which they are shaped-and misshaped; he threw perfect vessels and then folded and twisted them into unique and original forms. Bombastic self-promotion was a habit with Ohr, one which alienated him from his more restrained contemporaries in the art pottery and Arts and Crafts movements. It took the form of signs, broadsides, and public demonstrations, such as the Mardi Gras float in which he appeared as an old man bearing a huge cross.

He loved word games, and variously referred to himself as the Biloxi M. (mud dauber and pot maker), The Unequalled Variety Potter, Crank, Etc. And most memorably, The Mad Potter of Biloxi. He used his own name in numerous variations, calling himself the Pot-Ohr, Biloxies Ohrmer Khayam and Greatest Ohr-nament and his shop, the Pot-Ohr-E.

Many of his creations were inscribed with his memorable quotations, such as Potter sed-2-clay/B ware/and it was/a thing of the future. Over the years he accumulated nearly ten thousand "mud babies", which he boxed up around 1909 and put in the attic of his studio before turning it over to his sons, who converted the space into an automobile repair shop. Alone in his aesthetic, understood and appreciated by too few of his contemporaries, he was quickly forgotten after he gave up making pottery around 1908. Prior to the rediscovery of this trove by an antique dealer in 1969, Ohr was known only from a few turn-of-the-century articles and a handful of works in various collections. The rediscovery of his work coincided with a renewed interest in the art pottery movement and necessitated a re-evaluation of turn-of-the century American art history. Most recently, The Museum of Modern Art furthered this reconsideration of his genius, and the importance of his work in the history of art and craft, by displaying six of his works in a room displaying modern masterpieces by Seurat, Gauguin, and Van Gogh.